Off a winding rural route in southeastern Vermont stands a tiny house with a red door and sharply peaked roof. Inside, rubber boots line a narrow passageway to another door, which opens into a single subterranean room, revealing wooden boards stacked high. They’re crowded with cheeses: some fresh and naked, others with downy white or copper rinds, still others speckled ochre and grey. All are different dimensions of round—except for one corner filled with distinctive hefty squares.

These cheeses are unique, and not only within this underground aging cellar. They are part of a one-of-a-kind experiment that’s shifting the broader landscape of American cheese. They are Parish Hill Creamery’s version of Cornerstone, a collaborative effort to develop a new “American Original” recipe that is not the property of a single cheesemaker.

“We’re providing a platform. Anybody should be able to do it if they start with the same elements,” says Peter Dixon, Parish Hill’s co-owner and cheesemaker. “It’s the idea of having a common recipe out in the public domain,” echoes Mark Gillman of Cato Corner Farm in Connecticut. Together with Sue Miller of Birchrun Hills Farm in Pennsylvania, Dixon and Gillman make up the inaugural trio of Cornerstone cheesemakers.

Cows grazing at Birchrun Hill Farms

Encouraging Originality

In its annual competition, the American Cheese Society (ACS) recognizes the best-of-the-best among American cheese. The contest includes a category called “American Originals”—cheeses that are described as being “uniquely American in their original forms.” Within that group is a short roster of specific subcategories—brick cheese, brick muenster, Colby, dry Jack, Monterey Jack, and Teleme—a list that has remained static for decades.

There’s no shortage of inventiveness, artistry, and technical know-how among the nation’s cheesemakers, assures John Greeley, chair emeritus of the society’s Competition and Judging Committee; “people are making a lot of creative cheese.” But there’s a catch to establishing a new cheese type: “Achieving an American original is tricky because of ownership,” he says. In America, new cheeses tend to be created by single cheesemakers using proprietary recipes. That’s why the competition organizers created an additional American Original Recipe subcategory, for unique cheeses that don’t fit anywhere else.

But Greeley thinks that it’s high time the number of American Original subcategories expanded. At the society’s 2015 conference, he put out a call to makers to create more original recipes that could be shared among multiple cheesemakers.

Brian Civitello, co-founder and cheesemaker at Mystic Cheese Company in Connecticut, jumped on the challenge. Over beers after the conference, he proposed to Peter Dixon and Sue Miller that they work together to develop a new, uniquely American recipe and make it available to all. “I thought, Why not take the ego out it?” Civitello recalls. “That seemed to be the missing piece of the puzzle.” As the project developed, Civitello had to prioritize his own major business expansion and suggested bringing in Cato Corner instead.

Taste of Place

If Civitello was the initial ringleader, Dixon is the philosophical visionary. The highly regarded cheesemaker, teacher, and consultant started his first cheesemaking operation with his family in the early ’80s. Dixon went on to work for a who’s–who list of Vermont cheesemakers including Vermont Shepherd, Shelburne Farms, Vermont Creamery, and Consider Bardwell Farm. Early in his career, he partnered with a French cheesemaking company and later spent several years working on and off with seasonal sheep dairies in Albania and Macedonia. Learning the art of making native starter cultures from Swiss monks in Kentucky was revelatory. Since he and his wife, Rachel Fritz Schaal, started Parish Hill Creamery in 2013, they have completely eschewed commercial cultures.

Parish Hills Creamery Cornerstone

On a late fall morning, the day after the last make of their seasonal production cycle, the couple sits in armchairs in a plant-filled living room. Frequently bumping into each other’s sentences, they talk about Cornerstone and its connection to Parish Hill Creamery, which they run and co-own with Fritz Schaal’s sister, Alex Schaal. Smiling often from behind a grey-ginger, mountain man–style beard, Dixon uses his hands liberally for emphasis. His wife listens carefully, jumping in to add or clarify.

After Dixon arrived at a professional fork in the road a few years ago, Fritz Schaal recalls asking him, “If you were king, what would you do?” His answer? Make cheeses from the raw milk of a single herd cared for by a great farmer. Further, Fritz Schaal continues, “He said he wanted to make big rugged cheeses with his own cultures. I said, ‘That’s fine for a one-off, but nobody does that for real cheeses.’”

It turned out, however, that if anybody could do it, Dixon could. Working closely with Elm Lea Farm in nearby Putney, Parish Hill developed a line of award-winning, raw–milk cheeses made with cultures propagated from that same milk. “As pure a taste of place as we can make,” Dixon says with satisfaction.

Let the Milk Shine

When Dixon and fellow cheesemakers started brainstorming their American Original recipe, the first challenge was to grapple with the category. Many see it as a catch-all for cheeses that don’t quite fit elsewhere and are only slight tweaks on European recipes. (Even though, Greeley notes, ACS uses a six-point screening list to rate each American Original Recipe category entrant as “globally new and unique from all other cheese types.”)

Rather than starting with a style, the Cornerstone makers agreed that the project would be driven by “the taste of each of our places,” Dixon explains. “In a sense there is nothing new; every cheese has been made,” Fritz Schaal adds. “What makes it new is honoring your water, your grass, your land, your animals, the microbes on your hands and in your aging space.”

The team tasked Dixon with developing a set of guidelines and a recipe based on three fundamental pillars: raw milk, native cultures, and a natural rind. Each cheesemaker would source milk from their own herd or a single nearby herd and make their own starter cultures from that milk according to a method specified by Dixon (for more on how this works, turn to p. TK). Salt must be harvested from as near the cheesemaker as possible, calf rennet is used, and only turning and flipping wheels is permitted during aging (so as not to disturb the natural flora growing on the rind). Each maker uses the same stone paver–shaped form and, ideally, cheeses are aged for a minimum of five months.

The recipe is completely reliant on the highest-quality raw material. “You take what you have and figure out what it does best without messing too much with it,” Dixon says. “Everything’s kept so elemental—it’s about letting the milk shine.”

Sue Miller (far left), Peter Dixon, Rachel Fritz Schaal, and Mark Gillman working on the inaugural batch of Cornerstone.

From Scratch

In March of 2016, Gillman and Miller traveled to Vermont so all three could work together on the inaugural batch of Cornerstone. Both had taken cheesemaking courses with Dixon and were drawn to the project as a learning and collaborative opportunity. Gillman has made cheese for two decades with his mother, Elizabeth MacAlister, on their Colchester, Connecticut farm with the milk of their Jersey herd. While the cheeses have evolved over time, many of the duo’s initial recipes were inspired by European cheeses, Gillman explains; Cornerstone intrigued him because “it was never intended to replicate something.” Given the near-universal reliance on European freeze-dried cultures, learning to propagate local cultures feels valuable, he says. Gillman sees this as a bonus not only for his own professional growth, but—because of the opportunity to compare different versions of Cornerstone—also of potential benefit to the broader cheesemaking community.

Birchrun Hills Farm Cornerstone

Sue Miller and her husband, Ken, have been making cheese for about a dozen years from the raw milk of their mostly Holstein herd about an hour northwest of Philadelphia. Like most small cheesemakers, Birchrun Hills started by “taking European-style cheese and putting a twist on it,” Miller says. An enthusiastic team player, she leapt at the chance to be part of Cornerstone. “I love working together to take things to a higher level,” she says. “The beauty of it is that we’re getting to the beginning of the process,” Miller continues. “For me, Cornerstone is an expression of what we do at so many levels. It goes back to how we care for the land, how we care for the cows. It’s an expression of our milk in its purest form.”

High ideals aside, both Gillman and Miller acknowledge that making starters from scratch requires deep commitment and time they don’t always have. Gillman had to start fresh after his first Cornerstone batch failed due to a weak culture. “The biggest pain in the neck is making the cultures,” Miller says. “It’s too hard to do it if you don’t believe in it.”

New Model

The Cornerstone project is still very young in cheese years, but it’s already earned serious attention. Last year, Bon Appétit magazine named it one of the 25 most important cheeses in America. “Cornerstone promotes a new eco-microbio-political craftsmanship,” wrote cheese expert Carlos Yescas in the feature. “The result is a cheese that is connected to the land that produced it and an experiment in the creation of a new American Original.”

John Greeley is gratified by the collaborative and inclusive approach. “It is very promising, especially the fact that they’re willing to share and popularize it,” he says. Whether or not Cornerstone does succeed in becoming one of the new American Original subcategories Greeley envisioned, it’s likely going to yield insight into microbial terroir that will resonate throughout the cheese community.

Cato Corner Farm Cornerstone

At the University of Connecticut, food microbiology assistant professor Dennis D’Amico sees Cornerstone as an unprecedented opportunity to study how a “farm- and cheesemaker-specific selection of microbes” impacts a cheese. His lab is taking cheese samples from each maker throughout the production process. Some cheeses have been moved to a different aging cave in Vermont to mature side-by-side. In addition, microbiological analysis will be done on samples collected from each environment—including swabs from surrounding surfaces and people. An expert panel will also conduct descriptive sensory analysis of cheeses after six months of aging. “We hope to be able to track compounds in each cheese,” D’Amico explains, “and start to identify unique microbes that are responsible for unique flavors.”

Open-Source Cheese

Three years after that initial challenge was posed, the Cornerstone cheesemakers presented a panel and tasting session at last summer’s ACS conference. Their cheeses differed in some significant ways—but the makers believe there is a common underlying thread. Brie Hurd, cheese buyer and manager at The Cheese Shop of Salem in Massachusetts, has been able to offer Cato Corner and Parish Hill Creamery Cornerstone side by side at her counter. “There were definite distinctions, but they were similar in ways that had an obvious link,” she says. “They shared a round nuttiness in flavor, although Parish Hill had more of a bright, lactic tang and Cato Corner a more brothy finish.” Overall, Hurd enthuses, “I love the idea of setting really careful limits, maintaining that core integrity.” Many of her customers, the monger adds, “appreciate when we explain this cool thing we’ve been privileged to be a part of. It’s like a backstage pass.”

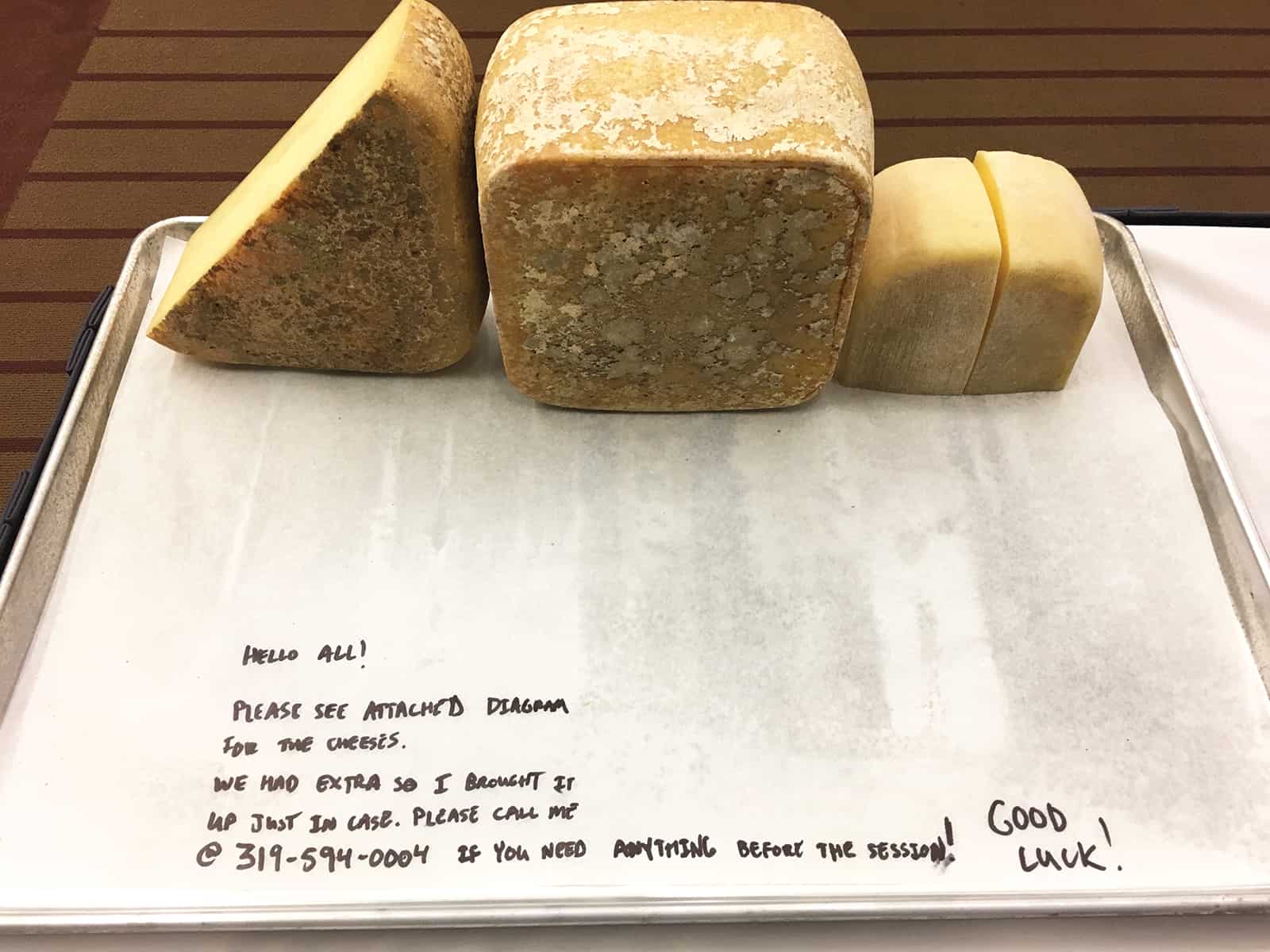

Left to right: Cato Corner Farm Cornerstone, Parish Hill Creamery Cornerstone, Birchrun Hills Farm Cornerstone

Moving forward, the cheesemakers are working on ensuring consistency within their own batches and on standardizing the recipe before sharing it with others. Some key pieces need to be worked out before the Cornerstone community expands: There will be a maximum production quantity for each cheesemaker, and the current handshake agreement will be formalized. It’s a balance between making the code open–source, so to speak, while assuring that standards are met. “If we want to create a category, we do need to standardize, establish some kind of protocol,” Gillman acknowledges, “but part of the point is to democratize it.”

While some have compared Cornerstone to a geographical indication, such as a PDO—Europe’s system of codifying names and recipes for certain regional foods and beverages—Dixon and Fritz Schaal clarify that Cornerstone’s mission has never been to create such a designation. “Homogeneity is not a goal. We don’t want yours to taste like ours,” says Fritz Schaal. The measure of success, the couple reiterates, is that Cornerstone cheeses are all deliciously different, representing what is unique to a particular milk and maker within the constraints of a basic recipe.

At the end of the day, Dixon hopes that Cornerstone will build cheesemaker interest in native cultures and provide a jumping-off point for more American Originals. “Ultimately,” he says, “the goal is that once they try it, they will be inspired to do their own.”