Photo by Matt Austin

Here in the States, we speak of third-, fourth-, sometimes even fifth-generation farms. In Devon, England, Mary Quicke runs a 14th generation clothbound cheddar operation, and it would not be a stretch to say that her fate was set by Henry VIII falling in love with Anne Boleyn in 1527. When the Catholic Church refused to grant Henry a divorce from his first wife, he divorced England from the Church, kicking off the English Reformation and triggering the redistribution of England’s monastery lands. One of Mary’s ancestors was the lucky recipient of some of that land, and the rest is dairy history.

On the land, Mary now crafts innovative wheels of an oak-smoked clothbound goat cheese, a Devonshire riff on Red Leicester, an Alpencheddar, and many vintages of her traditional cheddar; she’s also developed a cheese education program—called the Academy of Cheese—inspired by the American Cheese Society’s Certified Cheese Professional certification. She is a force, but her impressive resume doesn’t keep her from putting people completely at ease. When we spoke this spring, she was casually snacking on hot cross buns she’d made for Easter, getting emotional about Brexit, making plans to go surfing in Cornwall, and positively swooning over soil.

This interview has been edited for length.

culture: I always like to start by asking people how they got into the world of cheese, but on a 14th-generation family farm, that question sort of takes on new meaning! MARY QUICKE: Well, I guess it’s what Warren Buffet calls lucky sperm, doesn’t he?

[Laughs] Yes, that must be it. So, can you tell me how the Quickes got their start on their farm all those years ago in the sixteenth century?

MQ: Well, the start came from Henry VIII deciding he wanted to change his marriage plans…he fell out with the Pope, and the way that he got that resolved was to move away from the Catholic church and become a Protestant church, and the way that he sold that to his people, who otherwise might be thinking they might be going to hell, was to give out all the monastery land to the Lords. Then an ancestor of mine 14 generations ago married an heiress from that time. Her father had got some land and a Quicke from the middle of Devon married this lady and got this bundle of land.

And there would’ve been cheese made on the farm, but after about the first World War, we had stopped making cheese. So, in the sixties, you had to apply for a license to make cheese. [My parents] applied for a license and it was six, seven years or later that the license came through. At that point, my father was doing agricultural politics, so it was my mother who, as well as raising six kids, said, “Okay, sure. I’ve had the training to be an art student, and I’ve been told that is the training to do anything.” So, she built the cheese dairy and ran it.

And where are you in that lineup of six kids?

MQ: I’m the first daughter, second child. I think that’s the kind of bossy position.

Was it ever a question for you that you were going to go into cheese?

MQ: Well I’ve got three brothers, so I kind of assumed that one of them would come back to the farm. So, I went off to London and did a degree in English literature and did some radio and sold some news photographs for a living, and married. But I just wanted to come back to the farm. One evening, my husband had gone to bed and my father spoke really movingly about this wonderful mechanism of our farm, the cows eat the crops and the grass, we milk the cows, then make that into cheese and butter, and the whey goes to feed the pigs. And then the manure from everyone goes back to grow the crops and the grass. And I kind of loved that sense of this beautiful perpetual motion machine in this beautiful place. So I said, “Dad, could I come back to the farm?” Thinking, I’m sure he expects one of the boys to, and he said, “Yeah, that would be wonderful, but you have to go and work on another farm, and go to college.” And so, I went to work on a cheese farm in Cheshire and went to agricultural college.

Were any of your brothers ever interested?

MQ: Well, how come it’s gone through 14 generations on this bit of land, is that thing of primogeniture, where the oldest child, usually a boy, gets the land. So [my eldest brother] trained as a doctor, but he now runs the woodlands. About half of the land area here is woodlands, it was kind of rewilded in the 1880s, if you like “rewilded.” So, the woods are a really beautiful part of the farm. We’re looking at being carbon neutral and it really helps that we’ve got those woodlands. Not yet, by 2030, is what our target is.

What is the typical workday like for you? I heard that you surf!

MQ: I have to say, what I find about surfing is that, you need courage, strength, and stamina to surf. And as I age, I notice that these are fading and I’m becoming a beginner again. I’ve gone back to a beginner’s board again. But I’ve got no pride. Do you know what I mean? I just love being out in the ocean, you know?

Definitely. Have you been doing it since you were in college? Did you start young?

MQ: My dad took up surfing when nobody surfed, or nobody in this country surfed. So, we surfed when I was 12, I think, and we surfed on these enormous, like, ten-foot-six boards with no leash. So, if you fell off your board, you just had to kind of catch it.

When you’re not surfing, what is your typical day like working on the farm?

MQ: Well I used to milk cows and drive tractors and make cheese. But now I might be tasting cheese. We have an in-house grading system, we taste all the cheeses at three months old and 12 months old and make assessments. I spend a lot of my time talking actually, conversations with people about, is the milk right? Have we got the breeding right? And just now I was having a look at the woodlands with my brother. It’s a real privilege for me to walk with him as he’s kind of thinking out loud what his plans are. When the cows are inside, we bed them on woodchip, which keeps the animals dry but also, when you then use that dirty woodchip and put it back on the land, it really increases the soil organic matter and allows the soil microbes to access the phosphorus. I get excited about the soil. We’re just learning so much cool stuff about how soil works.

And, I mean, then there’s emails, as few of those as I can manage. And there’s a really cool project that I’ve created with some other colleagues in the cheese industry, very much inspired by the CCP, called Academy of Cheese. Its mummy is CCP, and its daddy is WSET (Wine and Spirit Education Trust), the Master of Wine program. So, we’re [making it] accessible to consumers as well as professionals and having four levels of certification. And a model of using training partners and having it online, which is amazing because over COVID we’ve now had about 3,000 people studying or having studied our level one and level two. We’re in the middle of writing level three. Over 80 different countries!

Crazy!

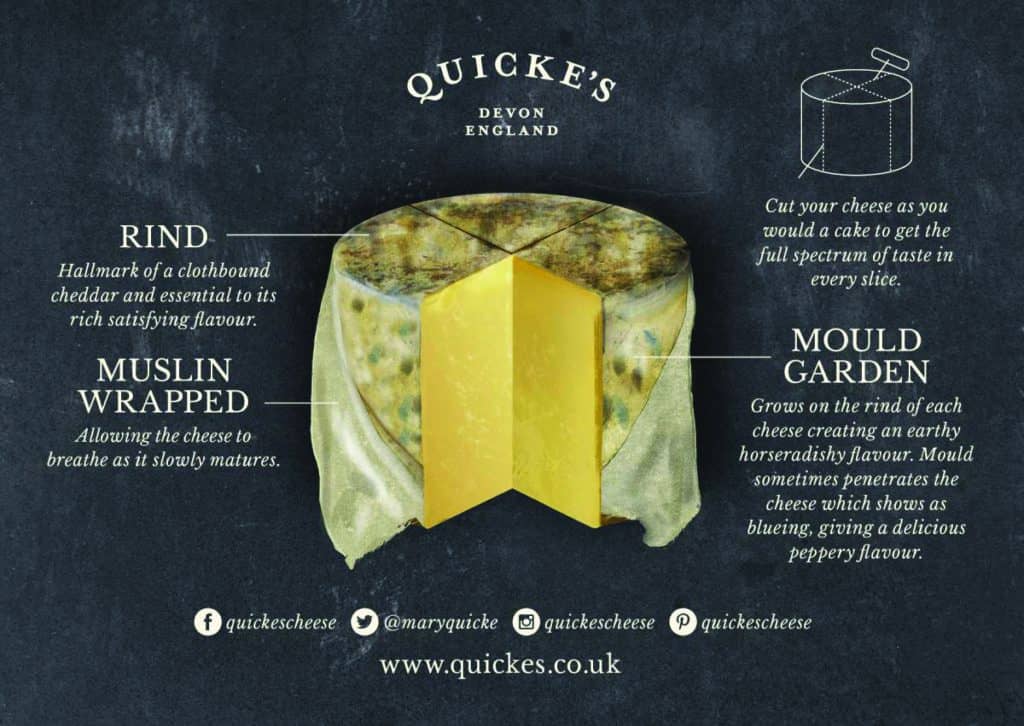

MQ: Yeah. I was very much inspired by coming and judging at ACS and learning about the CCP. One of the things we’re doing with Academy of Cheese in the level three on maturation and affinage, we thought we’d run a little competition where ten of our cheeses from an individual vat went out to eight different people. And they’re maturing them in different ways. And we’re going to be coming in 11 months later, seeing what that’s like. It started off because we swapped cheeses over with Jamie Montgomery, Montgomery’s Cheddar, and those cheeses became completely different. The Quicke’s at Montgomery’s tasted different to a Montgomery’s and a Quicke’s. So, we got the sense that there’s something really cool going on with that whole microflora that’s happening on the rind.

Can you talk me through the components that set your clothbound cheddar apart from say, another clothbound cheddar in the UK?

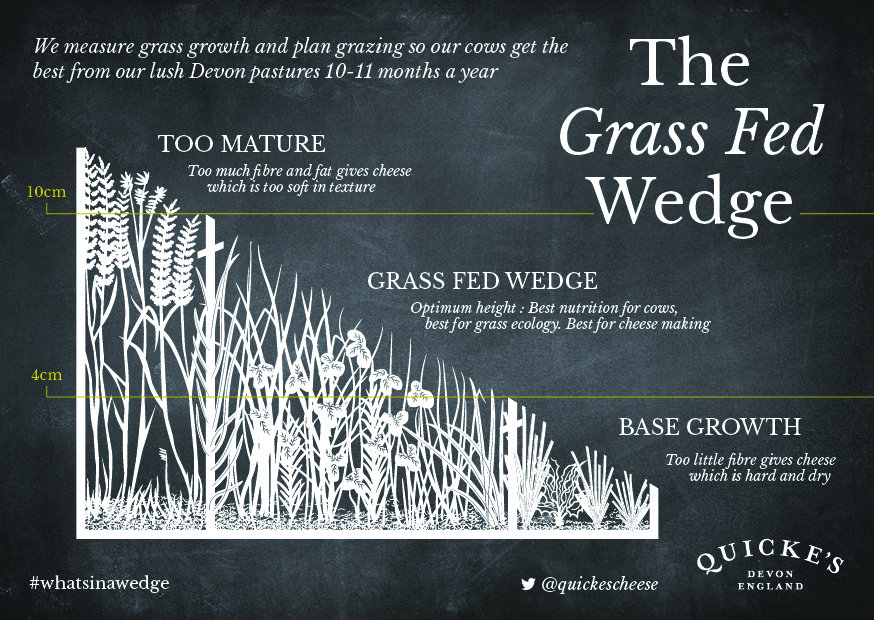

MQ: That’s a really interesting question because certainly milk from every farm tastes different. Of the cheddar makers, we are the ones who are using most grazing, our cows are outside, the spring calving cows are spending all of their milking time on pasture, the autumn calving cows, they come in for the winter, five, six weeks, to avoid the worst of the weather. So, we’ve got more of those grass-fed flavors. But also, because the fats are shorter chain, once you get cows grazing on grass, you get a sort of lusciousness of flavor, there’s a lovely melt-in-your-mouth, softer feel. All of the traditional cheddar makers, we all use these wonderful heritage starters, but there’s a library of about 400, and we tend to have our own ones that we use from that library, and they give quite distinctive flavors.

Jamie Montgomery has trained his customers that it’s fine if it’s got mold in it [laughs]. And we have not managed to do that! So, we tend to be much more careful. There’s lots of steps you can take to reduce the amount of internal mold, the blueing, the bruising, if you like. So, our cheese will tend to be quite low on bruising and that’s because we spend three days in the press and we double cloth, and all of that slightly changes the character of our cheese.

It’s so exciting to see all the makers who are using very similar methods, because then when you taste each one, you’re picking up on very subtle differences from the milk.

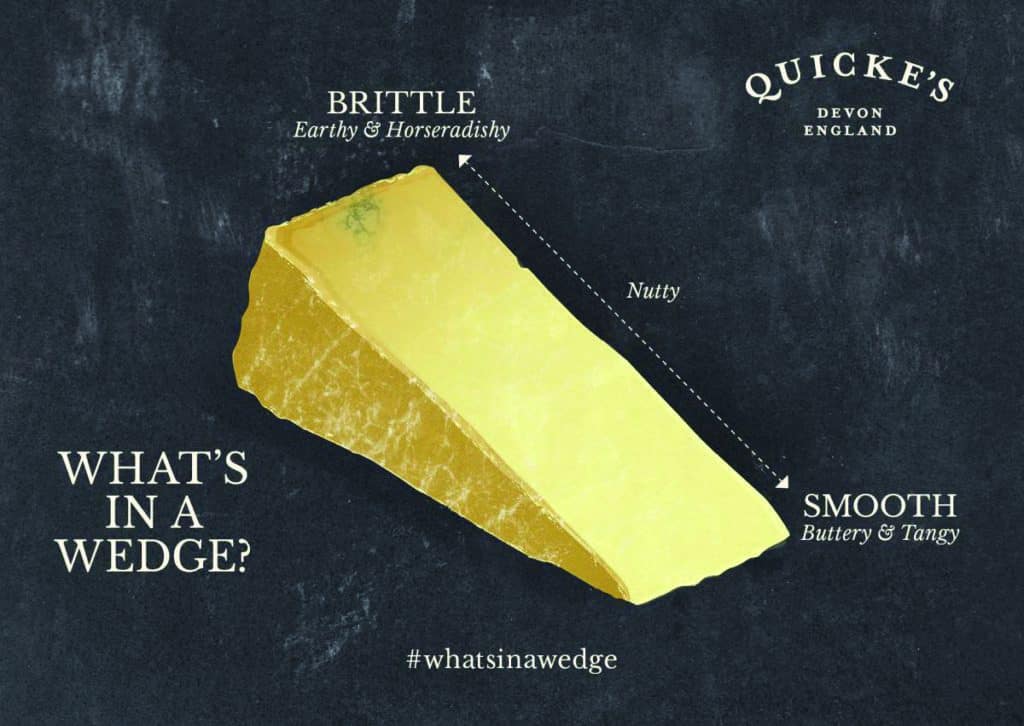

MQ: Well, and also, you get such a difference in flavor from the heart of the cheese and halfway back and under the rind. It’s really celebrating that, that tells the story of the cheese. It’s like a book.

Or like the trunk of a tree! How the middle of the trunk of a tree is younger.

MQ: Yeah! And driven by that loss of moisture through the cloths.

You got some press recently for speaking out about how Brexit was affecting farmers in the UK. How have your exports been affected by all that?

MQ: Certainly exports to Europe, we were doing them ourselves. We’d talk to some people and they’d give us an order and we would just put it on a lorry and off it went, where now it feels like we can’t do that. We need to work with other people, bigger companies who’ve got access to all the paperwork. I mean Brexit is just an enormous bit of self-harm, in my view, that Britain has done. I found myself being very kind of, really, really sad about that, ‘cause to me we’re just part of Europe. I found it completely heartbreaking. I cried about it! No, literally, when I heard that Beethoven Ninth Symphony, the Ode to Joy, which is the anthem of the European community, it still brings tears to my eyes to think of that. And I know that not everything out of Europe is… nothing’s perfect, but just that idealism and aspiration and countries working together. And I mean, I know this conflict in Ukraine is nothing to do with Europe, but was Russia emboldened by the idea of a divided West? Maybe a disengaged America and a fractious Britain? I don’t know. Who knows. Certainly where I was with Europe was, it was about that idealism and the idea that countries could work different but in harmony.

It’s like you were forced into exile.

MQ: [laughs] Yeah. Yes.

I’m curious if there’s anything about the artisan cheese community in the UK that you feel people in the American artisan cheese community don’t quite understand, or that functions differently over there than what you’ve seen here.

MQ: I had an amazing visit just now from Kerry Kaylegian. She’s an academic from Penn State in the world of both food safety and artisan cheese, she came and stayed with me. So that’s a real privilege, because we don’t have so many of those scientifically knowledgeable, technically capable, and practically engaged people in the UK. And I love that about the American cheese community. And here, we’re quite a close and small community. We have a Specialist Cheesemakers Association, which is a bit like ACS only it’s just for the little guys, which is very technically supportive, very good at having conversations with government and our food standards agency, and we have an amazing Specialist Cheesemakers farm walk, which is a weekend away where we go and visit some cheesemaker and have a little conference and a feast and a hangout, and most people camp.

A little cheese Woodstock!

MQ: It’s a cheese Woodstock! And it’s really kind of got that feel. Many beverages are imbibed. So, the thing I noticed, going back to Kerry, is that in America that artisan cheesemaking has got a sort of pioneer approach, people who want to be different and separate and not engage with the processes of government. Whereas I think the approach that we’ve taken is that we want to have government really understand us and get behind what we’re doing. You know, the Food Standards Agency, which would be like your FDA, I was a Food Standards Agency board member, because we need the correct regulation that’s gonna work for small businesses and that’s going to understand what artisan food is so that we can have a realm where, for instance, we can make raw-milk cheese. There’s no limit on the age of raw-milk cheese that we can make here.

Whereas the artisan cheese community in the US is, in some ways, a reaction against government-sanctioned cheese.

MQ: And that’s an interesting point, isn’t it? When we started making cheese again in the 1970s, we definitely wanted to make clothbound cheese. And people said to my mom, I don’t know why you’re bothering making that old-fashioned cheese, why don’t you make nice modern block cheese and you can grow much bigger? There was a bit of a time between the seventies and eighties when artisan cheese looked like it was the left-behind cheese. And then along came people like Randolph Hodgson of Neals Yard and Juliet Harbutt with the British Cheese Awards saying, “Hey guys, there’s some amazing flavors here. We mustn’t lose these. We mustn’t forget it.”

I think American cheesemaking industrialized far sooner than British cheesemaking. So maybe all of those cheeses that Americans must have made in their farmhouses in the early years of the twentieth century and before, whatever cheeses they would’ve come over from Europe with, those are kind of long forgotten, whereas in this country, maybe things weren’t so long forgotten. When we taste cheese to people in this country, older people would say, “Ah! That’s the cheese I remember from when I was a child!” I had one guy say, “I tasted your cheese and it changed the course of my life because I realized cheese could be unique and an expression of a place.”

That’s so lovely!

MQ: Isn’t it? People can start expressing what they want out of our food system with these things that are made by a person and coming from a place. The thing I’m getting really excited about right now is that we’re working with this extraordinary unknowable complexity of the soil, and we have these heritage starters. And the way that cheese maturation happens, it’s this incredibly complex process and you’ve got this unknowable complexity of the microflora around the cheese. So that’s kind of a reflection of the world we’re in where we’re starting to manage these processes of climate change and we just have to deal with the fact that we’re not the bosses! We’re the stewards of our world and we’re the stewards of our cheese and we’re the stewards of our food. Am I making any sense at all?

Yeah, it’s beautiful! You’re giving an inspirational speech!

MQ: You know, the older I get the less I know, do you know what I mean?

Yours is a great job to always be learning.

MQ: And any solution to climate change or environmental issues has got to involve food and has got to involve consumers saying, “I want my food to be this way and not that way. I want my food to carry these values.” And I can’t see how you can make soils work unless you’ve got an animal step in the system. We can’t keep just harvesting organic matter from the soil. I mean, that’s why people say there’s only 60 harvests left. And if you have an animal step in, then have that animal step be something that cycles nutrients through the system.

Speaking of future harvests, do you know who wants to step in and take over the farm when you’re no longer around?

MQ: My daughter is in the process, and I’m so happy that she’s joined the business. She’s so capable and she’s got that understanding of the scientific processes. I would consider it a real honor and a privilege if she felt that she wanted to join the business and take it forward. I know what I want, but in these multi-generational businesses, it’s really important that people don’t feel obligated. How you spend your life should give you the greatest pleasure and the greatest enjoyment rather than a sense of obligation. Work should touch you and inspire you and be something that fulfills you. That’s been the privilege of my life and I wouldn’t want anyone, particularly my own daughter, to be embarking on a future that didn’t hold those things.

You want someone who’s as excited about soil as you are.

MQ: [laughs] Well, or just… life is precious! This isn’t a dry run! There isn’t a real life ‘round the corner that we’re about to live, you know? Do what inspires you, ‘cause this is it! I see that now from this end of the telescope, have the best time ever! Eat the most delicious cheese, enjoy every bit. You can’t enjoy every bit, I didn’t enjoy the Brexit vote, or the day after the Brexit vote.

The downs make the ups that much better.

MQ: Well, and shit happens. I don’t know if you can write that, but stuff happens. And then it’s about how you are about it. Isn’t it?