World Cheese Awards provides the opportunity for a turophile tour

When I was invited by the UK-based Guild of Fine Food (GFF) to attend the International Cheese Festival in Oviedo, Spain as a judge at the 33rd-annual World Cheese Awards (WCA), I decided to make the trip into a week-long educational journey. I would start and end in Madrid, covering some 1,000 miles in the central, northern, and eastern parts of the country, visiting a total of six cheesemakers before and after the awards on Nov. 3. The following are highlights of a whirlwind week.

Sunday, Oct. 31:

Because Nov. 1 is All Saints Day, a national holiday in Spain, after landing at 9:45 a.m. my partner, (and de facto photographer, Jeff Leyden) have to hit the ground running. It’s gray and drizzling as we drive out of the Madrid airport and I’m grateful for the lack of traffic. Slightly bleary from the overnight flight, I’m also thankful that for the first cheesemaker visit I will be accompanied by a translator who not only speaks English, but is also familiar with the complex territory of Spanish cheese. Enthusiastic, kind, and immensely helpful, Mar Sanz was recommended by Carrie Blakeman of Rogers Collection, one of two importers I worked with to plan my itinerary (the other is Forever Cheese). Mar and Joaquin Manchado Munoz, owner and cheesemaker at Moncedillo, are waiting at a highway gas station to guide us into the tiny hamlet of Cedillo de Torre in Segovia, where Joaquin’s operation is located.

But first, we have to see the sheep. We bump down a dirt road between fields to a long barn, where pregnant ewes and their lambs rustle about in large, hay-filled pens. They belong to the farmer’s 1,600-head herd of Churra, an ancient, now-rare breed that originated on the Iberian peninsula. Their milk is traditionally used for Zamorano, but Joaquin uses it to make three raw-milk cheeses: Moncedillo Original (which won Gold at the WCA), Red—dusted with spicy, smoky Pimenton de la Vera paprika—and Madurado (aged). At his creamery, he explains that he and his wife, Esther Garcia Rodríguez landed on cheesemaking as their “rural Plan B” following long careers in the film industry. Both Esther and Joaquin have worked extensively with celebrated Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar, she as a producer and he as a cinematographer. Joaquin studied with a master affineur and found that the creativity involved in making cheese mirrors that of making films. “I believe that whatever you do, do it with enthusiasm and do it well, or don’t do it,” he says.

- Pregnant Churra sheep in the lambing barn

- Joaquin Munoz, owner and cheesemaker at Moncedillo, with his sheep’s milk cheese

- Moncedillo Original and Red in the drying room

- With Munoz and translator Mar Sanz

Tuesday, Nov. 2

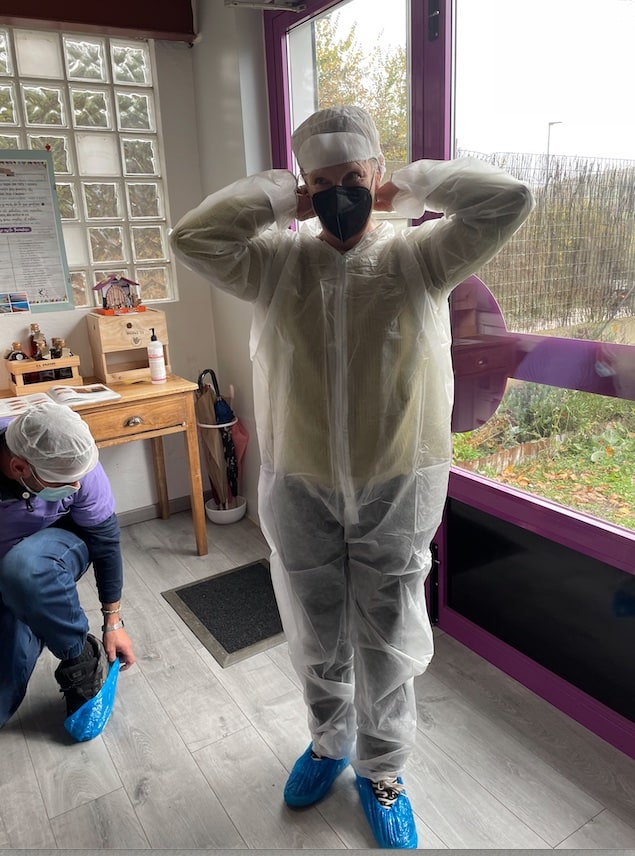

Following a few hours to catch our breath touring the old city of Segovia on Monday (in the sunshine!), we drive nearly three hours north to León and spend the night there to visit another small and fascinating cheesemaker on the outskirts of the city. In the valley town of Robles de la Valcueva, Oscar Fernando Marcos Gonzalez and his assistant, Ana, make goat cheeses at La Facendera, which in Leónese dialect means working collaboratively with your neighbors on a project to benefit the community. I find them in their cheerful shop that fronts the creamery, Oscar wearing his signature purple scrubs and what I can tell is a big smile behind his mask. He is representative of a younger generation of Spanish cheesemakers who have resurrected time-honored cheese recipes and modernized them. Discovered by importer Michele Buster of Forever Cheese 20 years ago, he worked with her to recreate a traditional, lactic-fermented goat cheese of the region, Babia y Laciana, with a less-acidic flavor profile than the original. Forever Cheese now imports his signature versions—Leonora, which has a bloomy white rind surrounding a dense and creamy center, and Leonora a Fuego, rubbed with Pimenton de la Vera before it ages so the white rind forms on top. We sample these cheeses along with others that Oscar does not export to the US: smaller goat cheese bricks flavored with marrons glacé, pesto, and black garlic, washed down with Ana’s homemade fortified wine. They send us on our way with a cheese care package for the road and directions for a scenic route to our next stop.

- Suiting up to visit the creamery at Quesos La Facendera

- Oscar Gonzalez and his assistant, Ana, with their Leonora a Fuego, dusted with Pimenton de la Vera

- Oscar cuts samples of Leonora for us to taste

- With Oscar and Ana in the tasting room

It is raining again and the skies are dark as we wind through a dramatic, mountainous landscape on the way to Pravia, in the Principality of Asturias. Some of the peaks are snow covered, but the valleys are green and lush, and a park in the center of Pravia is landscaped with flowering plants and palm trees. We meet Ernesto Madera López, master cheesemaker at Rey Silo, located in a tidy industrial area just outside of town. He and Pascual Cabano launched the creamery in 2005 to make raw milk versions of Afuega’l Pitu, one of five DOP cheeses made in Asturias. Using cow’s milk from a single farm, Rey Silo’s cheeses are simply called Blanco and Rojo, the latter of which has zesty paprika added to the paste, rather than on the rind. Ernesto also makes a larger, seasonal variation of the Blanco, called Massimo Magaya de Sidra. It spends its final two months of aging sealed in a barrel with apple must—the bits left over from pressing apples for cider. He proudly shows us his man-made cave in the basement, where wheels of Rey Silo blue cheese rest on wooden shelves. Behind the brick walls is a system normally used for radiant heating in floors; Ernesto has adapted it with cold water to mimic the conditions in a natural cave. A raw milk version of DOP Cabrales, the cheese was conceived in partnership with renowned chef and humanitarian, Jose Andres, a native of Asturias who is now a partner in Rey Silo. It is named Mama Marisa for the chef’s mother, and I was lucky enough to taste it at Rogers Collection, shortly after it first arrived in the states.

- Master cheesemaker Ernesto López explains his process at Rey Silo

- Rey Silo’s blue cheeses aging in the man-made cave

- Tasting Rey Silo Blanco and Rojo

Later that evening in Oviedo, the mood at the welcoming reception for WCA judges is like a class reunion, with old friends reconnecting over Asturian cheese and cider. The room is filled with luminaries: there’s Dave Gremmels from Rogue Creamery, sporting a bright blue jacket with “The World’s Best Cheese is Handmade with Love in Oregon,” on the back. (Rogue River Blue won the last World Cheese Awards in 2019.) There’s Jessica Fernández and Carlos Yescas from Lactography in Mexico City, Mary Quicke from Quicke’s Cheese in Devon, UK, and Cathy Strange, the global cheese buyer for Whole Foods. And of course our hosts, Tortie and John Ferrand from the GFF. We make an early exit to rest up for the big event the next day.

- Asturian cheeses at the welcome reception

- With Michele Buster of Forever Cheese (center) and Mary Quicke of Quicke’s Cheeses

- Nick Bayne, head cheesemonger at Fine Cheese Co. in Bath, UK, and Jessica Fernàndez of Lactography in Mexico City

- With the great Dave Gremmels

Wednesday, Nov. 3

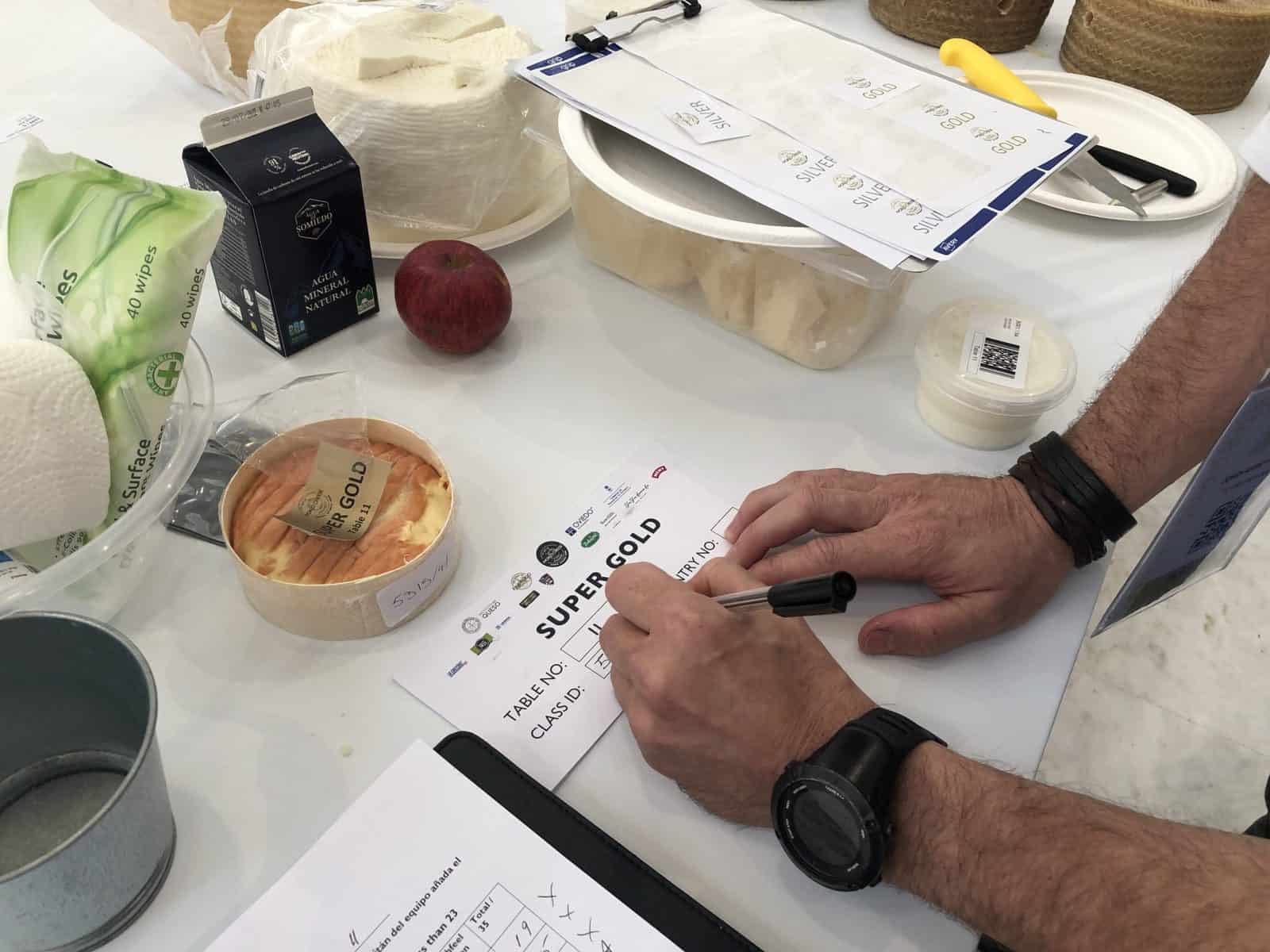

Sporting our blue cheesemonger aprons, the judges—230 of us from 37 countries—file into the huge auditorium at Oviedo’s impressive Palacio de Exposiciones y Congresos (which along with the hotel attached to it was designed by architect Santiago Calatrava) for a briefing on our judging responsibilities by John Ferrand. The sound of live music is our cue to make our way to the judging area, and like Olympic athletes entering a stadium we descend a staircase flanked by members of a traditional Asturian band playing bagpipes and accordions, while TV cameras and photographers capture the scene. There are 4,000-plus cheeses laid out on long tables; I’m at number 11, where I meet my judging partner, Jordi Arroyo Vicente, a former cheesemaker, now a consultant, who has done this gig before. He speaks next to no English, and my Spanish is minimal, so we make do with translation apps on our phones. Our job is to smell, feel, and taste the 45 cheeses on our table and to score them using a point system, then award bronze, silver, and gold to those that qualify. We are also tasked with choosing one Super Gold cheese that will go onto the next level of the competition. Ours is an easy decision: a washed rind round in a wooden box that I can’t stop dipping a spoon into. (I later learn it’s Epoisses Berthaut, washed with Marc de Bourgogne.)

- Judges find their tables

- The newbie

- Jordi uses a cheese iron to extract a sample of Gouda

- Tools of the trade

- Choosing our Super Gold cheese

- The winning cheese, Olavidia

The 16 “super judges,” deeply knowledgeable cheese professionals from 15 different countries, retreat to a room to determine which of the 88 Super Golds will make it to the final round, held live on stage in the impressive auditorium. In front of a large and eager crowd, each judge champions one cheese; they all taste the cheeses once again and vote. The last cheese tasted, championed by Jason Hinds of Neal’s Yard Dairy (who says, “it winked at me”) is the ultimate winner: Olavidia, a square, bloomy-rinded goat’s milk cheese with a layer of ash in the center, made by tiny Andalucian creamery Quesos y Besos. The cheesemakers are feted later that evening at a gala dinner prepared by Michelin star chefs, hosted by the Asturian government and, thankfully, featuring very little cheese.

Thursday, Nov. 4

We’re off on a short press trip to explore eastern Asturias, where the region’s two DOP blue cheeses, Cabrales and Gamoneo, are made. Following a visit to the Cabrales cave, we have lunch at Sidreria Casa Niembro (a cider bar and restaurant) in the picturesque mountainside hamlet of Asiegu de Cabrales. In accordance with local tradition, the owner pours his cider from a height to add bubbles; it accompanies a rustic and extraordinary meal that starts with Asturian cheeses and charcuterie and continues with puffy cornmeal and chorizo tortos, fabada (a regional bean stew with blood sausage, chorizo, and pork), locally raised lamb in a cider sauce, nougat ice cream and rice pudding brulée. We could easily stop there and call it a day, but our hosts, the Asturian tourism board, have more excellent food in mind. Dinner is at the beautiful, Michelin-star El Corral del Indianu in Arriondas, where chef/owner José Antonio Campoviejo wows us with course after course of astonishing small plates. Eating a lot and well is the Asturian way, apparently.

- Entrance to the Cabrales cave

- The owner of Sidreria Casa Niembro pours his cider

- Cabrales and local charcuterie

- Asturian cheeses

- Lunch at the sidreria

- An unusual liqueur made from Cabrales whey

Friday, Nov. 5

It’s another grey, chilly morning as the press trip van climbs up a narrow road past mountain fields where dairy cows graze with bells around their necks, on our way to one of the Gamonedo caves, Cueva Oscura in Avín. Less-well-known outside of Spain than Cabrales, Gamonedo, which is made from 80 percent cow’s milk, 15 percent goat’s milk, and 5 percent sheep’s milk, has blue streaking close to the rind, but not throughout the cheese. To be designated DOP, it must be aged in natural caves, which are not open to visitors, so we feel fortunate to be allowed a peek inside, where cheese wheels in several sizes wait on shelves to reach their ideal ripeness, usually around five months.

- The mouth of Cueva Oscura

- View from outside the cave

- No crawling necessary …

- The cave’s limestone walls are key to the cheese ripening process

- For Gamonedo to be DOP it has to be aged in a natural cave

- Cheese from several Gamonedo makers are aged in Cueva Oscura

- Cheese journalists Kristine Jannuzzi (left), and Emma Young with tour guide Ernesto Fernández

- Cow pastures in Asturias

We say goodbye to new friends from the press trip (and our excellent guide, Ernesto Fernández of showmeasturias.com, who also helped us arrange the COVID test needed to reenter the US) and leave Asturias on our way to Haro in La Rioja. Our destination is Lácteos Martínez, a family owned creamery founded in 1961 also known as Quesos Los Cameros. It’s flagship cheese is PDO Camerano, a goat’s milk wheel that has been made in this region since the 13th century, Now operated by the founder’s children, CEO Sonia Martínez, master cheesemaker Javier Martínez, and their two brothers, the creamery is a large, modern facility that produces 2,000 tons of cheese per year, including sheep’s milk, cow’s milk, and mixed milk varieties. The three milks are also used to make one of Los Cameros’ high quality deli cheeses, Riojana. Machines turn the pallets of cheese in the aging rooms, but all of Los Cameros’ artisan wheels are hand-rubbed with olive oil every 35 days during the process. This, plus the woven pattern created by the basket-shaped molds give the cheeses a distinctive natural rind. The company’s thoughtful sales manager, Mario Pérez, meets us later for a glass of wine and shows us around Haro, notably the narrow streets lined with wine bars.

- Quesos Los Cameros Sales Manager Mario Pérez with PDO Camerano in one of the aging rooms

- Cheeses going into the brine “swimming pool”

- A wall of cheese

- Wheels are rubbed by hand with olive oil several times during the aging process

- The tasting room at Los Cameros

- Cheesemaker and co-owner Javier Martínez

- Mario at a wine bar in Haro

- Haro’s town hall. The small city is the capital of La Rioja

Saturday, Nov. 6

We can’t leave Rioja without visiting a winery, and Haro (the capital of the province) has several in a dedicated section of town. We stop in for a tasting at Bodegas Bilbainas, before hitting the road back to Madrid and one last cheesemaker visit at Quesos La Cabezuela. We’re deep in a residential section of the city when we realize we’ve made a mistake. The address to which we’ve navigated is one of La Cabezuela’s small shops; the creamery is out in the countryside, 45 minutes away. On a boulder-strewn hillside in Fresnedillas de la Oliva, we finally locate the small creamery—the oldest in the communidad of Madrid and the only one in its western section—where cheesemaker Juan Luis Royuela and his wife, Yolanda Campos Gaspar, are graciously waiting for us. They both spent years in other careers before buying the business, and unlike the original owners, they do not keep their own goats; the milk comes from herds of Guadarrama goats that live in the nearby mountains. Passionate and somewhat of an iconoclast, Juan Luis studied cheesemaking in the UK with Mary Quicke and at the Black Sheep School of Cheesemaking in Vermont. He believes that cheese should not only taste good, but be good for you; some of his cheeses, such as the ash-coated Minero (miner) are fermented with goat kefir. “My idea is that I’m cooking milk, interpreting recipes,” Juan Luis says. His goat cheddar is inspired by Lincolnshire Poacher, but he doesn’t call it cheddar, “because people say, ‘This doesn’t taste like cheddar; it’s not good.’” Instead the cheese is named Roy, a “queso madurado in montana (cheese matured in the mountains),” he says. La Cabezuela also produces Tradicional Semi-Curado, a natural-rind wheel; Lingote Cremoso, a brie-like cheese in the shape of an ingot; and La Cabra de Botas, a pillowy pyramid with a geotrichum rind. The last two came home in my luggage, and we are slowly enjoying them to make them last.

- Juan Luis Royuela explains how he makes his ash-coated cheese, Minero (Miner).

- La Cabezuela’s lactic fermented cheeses in the ripening room

- Wheels of Roy, a goat cheddar modeled after Lincolnshire Poacher

- Yolanda Gaspar and Jean Luis launched Quesos La Cabezuela 11 years ago

Cheeses available in the US

Imported by Forever Cheese

Gamonedo DOP

Quesos La Facendera: Leonora, Leonora A Fuego

Quesos Los Cameros: Camerano DOP, Los Cameros Mixed Milk Cheese, Oveja Anejo, Riojana, Senorio de Vaca Anejo

Imported by Rogers Collection

Moncedillo: Original, Red, Madurado

Rey Silo: Blanco, Rojo, Massimo Magaya de Sidra

Quesos La Cabezuela: Roy, Lingote Cremoso, Tradicional Semi Curado