Illustrations by Beatriz Gutierrez

1. The Theobroma cacao tree grows year-round, clustered on either side of the equator. Its flowers are pollinated by flies called midges; 5 to 7 months later, football-shaped pods appear.

2. These large pods sprout directly from the trunk and range in color from purplish brick to French’s mustard yellow. Like an apple, color is irrelevant to their ripeness—a mature pod sounds like maracas when shaken, as the seeds inside separate from the walls over time.

3. When pods are cracked open (often with a machete),the almond-shaped beans inside are covered in a sweet white pulp.

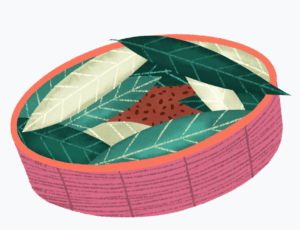

4. Like most good food, cacao is fermented. These wet beans are put into baskets or wooden boxes, covered with lids or banana leaves, and left to sit in their own goo for about a week to develop flavor.

5. Beans are dried by the heat of the sun on a flat surface. (In countries with prolonged rainy seasons, beans can be dried using artificial methods.) Once dry, they’re bagged in burlap and sent to chocolate makers.

6. When beans arrive, most chocolatiers roast them to coax out flavor (raw chocolate makers skip this step).

7. The fibrous husk around each bean is removed by a winnower that cracks shells open, then uses a vacuum-like vortex to separate them from the nibs inside.

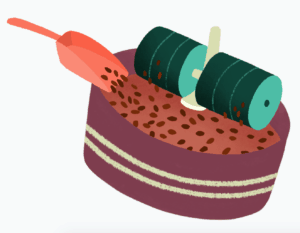

8. Nibs are ground into a paste (called cocoa mass or cocoa liquor) using stone rollers, then further smoothed in a machine called a conch. Some makers skip the conch step, while others age chocolate post-conch to develop flavor.

9. To make glossy, snappy bars, chocolate must be tempered—a process that raises and lowers its temperature to achieve a specific crystalline structure.

10. Tempered chocolate is poured into molds, which are vibrated to remove air bubbles before cooling and packaging.

DID YOU KNOW?

There’s a long-held myth in the industry that all chocolate can be lumped into three varietal categories: criollo, trinitario, and forastero. As the story goes, criollo is delicate, rare, and prized for its depth of flavor. Forastero, on the other hand, mightily resists disease, but lacks complexity. Trinitario, a hybrid of the two, lies somewhere in between. The effect of this distinction has been that criollo gets upsold, while forastero is maligned as cheap commodity chocolate.

In truth, there are at least a dozen varieties, all impacted by where they’re grown and how they’re processed. Geneticists discovered 10 varieties when they mapped the cacao genome in 2008, and each year more are uncovered—or created. “One of the key things to consider in cacao is [cross-pollenation] and the developing of new clones,” said Vicente Norero, owner of fermentary Camino Verde. “Most of the plantations have natural hybrids…the cacao trees have evolved and adapted to new weather and soil conditions.” To hear Norero tell it, genetic types are just a small component of top-notch cacao, affecting final flavor as much as soil, climate, fertilization, and fermentation techniques.