Recently marking their centennial milestone, Widmer’s Cheese Cellars of Wisconsin stands as a testament to resilience, dedication, and the preservation of cheesemaking as a time-honored craft. The family-owned business has produced its renowned Brick cheese using the same methods in the same location since 1922.

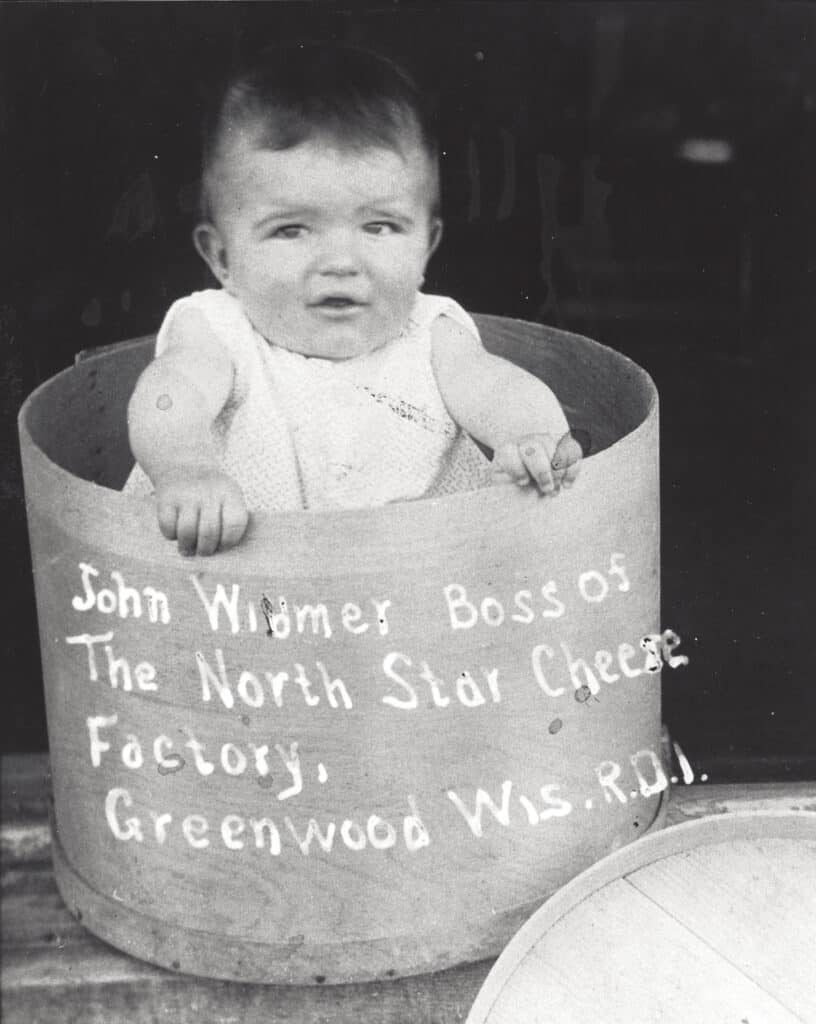

Founded by Master Cheesemaker Joe Widmer’s grandfather John Widmer, an immigrant from Switzerland, the Widmer’s began making surface-ripened Brick cheese to satisfy the predominantly German community. Fast forward to today, and the demographic has shifted. While the demand for traditional Brick has waned, Widmer’s remains dedicated to the family’s heritage—still using real bricks in the cheesemaking process—while continuing to innovate and craft new cheeses.

Now, Joe’s son Joey emerges as the fourth-generation cheesemaker, living above the cheese factory in Theresa, Wisconsin, just like his predecessors. culture sat down with the father-son duo to talk about their heritage, future aspirations, and the challenges of balancing their cheesemaking legacy with modernity.

Culture Magazine (CM): First, I want to say congratulations on your recent centennial celebration. Keeping a business running for 100 years is impressive, and even more so considering you’ve been able to keep it in the family.

Joey has recently taken over as Vice President of Operations. Can you tell me about what each of your roles are currently?

Joey: I’m essentially managing the entire company, and we’re a small business so I wear many different hats. Cheesemaking is the primary thing we do here, but we also have a cheese retail store, milk receiving, packaging, and an online website for mail orders.

Brick and Colby, our primary cheeses, are both Wisconsin originals, so we’re proud of carrying on that tradition. We also make Matterhorn Alpine cheddar—we’re really proud of that one because we created our own recipe that is different from every other cheddar. And we started making butterkäse in January 2023. That’s a very traditional German/Swiss cheese that not many people make, so I figured we would try to tackle that as well.

That’s pretty much what we do in a nutshell. We’re small and want to stay that way so we can produce a quality product.

CM: What about you, Joe? Do you still have an official role in the company, or are you there in an unofficial capacity?

Joe: Well, I sleep till noon. I’m semi-retired, I go up north to our cabin a lot, but I bring my laptop along and am always a reference for consulting. And I am here quite a bit this time of the year since it’s the busiest. So yes, I’m still here.

These guys are coming out with new cheeses. I know a lot of people in the industry, so I put them in touch with people they could talk to and get starters and bacterias that they need to make these different cheeses. But they do the actual cheesemaking and experimenting. I’m just kind of in the background.

CM: When did you start working in the family business?

Joe: I started when I was six years old. I’d walk into the plant and my dad and my uncle Ralph would say, “You’re the guy we’re looking for.” They had jobs for me already. And I think I was the kid in the family who was probably the most interested at that point. And I’ve been working there ever since.

CM: Joe, you’re a certified Master Cheesemaker in Colby, Brick and cheddar, right?

Joe That’s correct. I was one of the first back in the late nineties.

CM: What goes into getting that certification?

Joe: You must be licensed for 10 years in making a type of cheese, and then you have to take required courses. There are a lot of people making cheese that are taking pHs and checking the consistency at a specific time, putting it into brine at a specific time, but they don’t know the science and chemistry behind it. So, they go to the Master Cheesemaker Program to learn the science behind it—what makes the cheese do what it does.

I think there are only around 60 Masters out of 1,100 licensed cheesemakers in the state. Those guys go back to the plant and share their information with the people there. It’s a win-win for Wisconsin. There’s only one other country that has a program like that, and

it’s Switzerland.

CM: Joey, do you have your sights set on becoming a Master Cheesemaker like your father?

Joey: I do. I’m definitely working toward becoming a Master Cheesemaker. I think I have most of the courses done, but I just have to wait two or three more years before I can actually apply to the program. I think I would become a Master in Brick first and then go from there.

CM: Widmer’s is the only cheesemaker in the country that still uses real bricks in the make process. What inspired this dedication to tradition, and how does it affect the cheese’s flavor or quality?

Joe: This is more of a touch, feel kind of thing. These people are right at the vats. It’s not—and I’m not cutting on machine-made cheese, there are a lot of good ones out there—but it’s actually hands-on, artisan, authentic, that type of thing. And it makes a higher-quality product, just like going back to family recipes being carried down. If you start taking shortcuts or adding different, cheaper ingredients, you don’t end up with the same product.

We’re so authentic that we’re using the same bricks my grandfather used, and we follow the same recipes. When I was a kid, the hooks and everything were wooden—everything is stainless steel now. But we’re using the same recipes.

CM: Widmer’s still uses the same 12,000-square-foot facility that Joe’s grandfather bought in 1922. I read on your website that the facility has been “grandfathered in” on certain things—open vats, real bricks, and wooden curing racks—due to its age. Can you elaborate on what that means and how that impacts your decision to expand?

Joe: The original cheesemaking part of the building—the open store and cement salt brines, which we fiberglassed—all of that is stuff of the past, and we’re grandfathered in with that. But we have expanded quite a bit with our packaging area, warehousing, and an extra couple vats.

CM: So, if someone were to build a new facility today, they would not be allowed to build it in that same way.

Joe: That’s correct.

CM: And how does that impact your decision to expand? Do you want to continue producing at the capacity your current facility can handle?

Joe: Well, I stuck with it but it’s up to these guys if they want to modernize. So far, we have stayed this way, but that’s entirely up to them. I’ll be 68 in January, so what they want to do is their business. They’re probably getting a little sick of me butting my nose in once and a while. It’s up to them.

CM: Joey, do you have any thoughts on that?

Joey: Yeah, I mean, I would like to make it more ergonomic. Especially in today’s society, I think people are less willing to do hands-on labor or work that is difficult from a physical perspective. So, I think that will continue to be a challenge.

CM: So that might mean trying to streamline production?

Joey: Yeah. There are a lot of other jobs available where someone can pay just as much and probably not work as hard physically. I think every cheesemaker kind of has the same issue, from what I hear from friends in the industry.

CM: Finding that scale that works for your bottom line, physical wellbeing, mental wellbeing, and a production standpoint is still a bit of

a mystery.

Joey: I think so. I try to make sure that I have other outside hobbies, and on the weekends I try to distance myself from the business so I get a break. I realize that in the past that probably wasn’t the case here. My grandpa and great uncles were probably here every day, but I think there’s been a big shift in how people want to live their lives and, you know, have free time and everything. We try to provide that for our employees as well.

CM: I love that you brought that up. Joey, you’re currently living in the apartment above the facility, so you must be very intentional about getting that separation from work.

Joey: Yeah, I try to look at the positive aspects of it. And one of the positive things is that because of how early the start time is, I don’t have to get up as early to be at work.

CM: Right. You can’t beat the commute.

Joey: You can’t. But the negative aspect is that you don’t get that 15- or 20-minute drive that a normal person would have to and from their job to decompress. And then in my circumstance, if there’s other stuff that needs to be done and I remember it at 5:30 or 6:00 at night, odds are that I’m back down here trying to finish it.

Joe: Every family lived above the factory at one point. We lived up there until Joey and my daughter were eight and two years old, and then we built a house and [the apartment] was empty for a while. Now, Joey’s the fourth generation living above the plant. Sometimes, yeah, it’s too close to work.

CM: This question is for both of you since you were both raised by cheesemakers. Some kids are excited to follow in their family’s footsteps, while others yearn to chart their own path. When you were a young child, did you envision the day you’d take over the family business, or did it come to you later in life?

Joe: I’m somewhat surprised. I had other interests. In high school my dad said, “You want to make cheese or go to school.” That was in the seventies—I had a ponytail. I said, “Neither. I’m sick of school, I’m sick of cheese.” So, I went and worked on the railroad for a couple years. And when I’d come home, my dad didn’t push me, but he encouraged me to get a degree in food science. I thought that was a good idea, so I went to college, and I’ve been here ever since.

Joey: I always had other interests as well—mostly conservation and wildlife stuff. I went to college for business and worked at a couple of other places and ended up coming back here because the business always needed help. When I came back, I got more and more involved. And before I knew it, I’m going on my 10th year full time.

Joe: I might add, if Joey wanted to leave, he could leave pretty easily because he got a Master’s in Business Administration.

Joey: Yeah, but I do take pride in the name and quality product we have. There are times I consider doing something else, but this is what I’m doing now, and I’m doing the best I can with the tools I have.

CM: Do you have any hopes for the next 100 years of Widmer’s—if that’s not too far out to envision?

Joey: If we can maintain what we have and keep it sustainable without drastic changes to the product, that would be good. Keep the tradition but make small modernizations that would make my life simpler—for the employees as well. But as far as 100 years go, I’m taking it a decade at a time.